What is genocide?

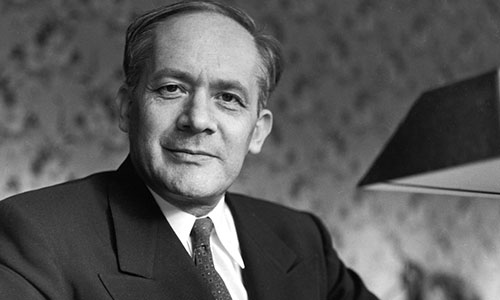

In 1933, the lawyer Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew, urged the League of Nations to recognize mass atrocities against a particular group as an international crime. He cited mass killings of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during World War I and other events in history. He was ignored. A few years later, the Nazi regime murdered more than six million Jews, including Lemkin’s own family. In 1943, Lemkin created a new word to describe such mass killing. He combined the Greek and Latin words, ‘geno’ (race or tribe) and ‘cide’ (killing). He proposed the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, approved in 1948.

Genocide does not only involve direct violence. It can involve creating conditions – such as starvation – that will kill people. It is usually committed by a government or a group of individuals with political and military power. The 1948 Convention has universal character because it confirms principles that are so fundamental that no nation may ignore them.

Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

- Deliberately inflicting conditions calculated to bring about its physical destruction

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

From Article II of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

When is genocide possible?

Genocide is possible when the messages of hate from would-be perpetrators go unchallenged and when the people at risk fall outside the awareness – and/or the sense of moral obligation – of anyone who could help to ensure their protection. International decision-makers are likely to be quite well-informed about what is happening, but need pressure from constituencies – the public and the media – to encourage them to prioritise and to give them the leverage to act. The public doesn’t know what the media doesn’t tell it. And the media doesn’t cover if it’s difficult and no-one is interested. This can lend itself to a vicious cycle of isolation for the victims. Often much more important than international factors, though, are the constituencies of the decision-makers responsible for perpetrating mass atrocities. If the population or group they depend on to sustain their power does not accept their hate propaganda, and acts instead in accordance with basic human values, this can significantly impede or even halt the course of a genocide.

Breaking the mould

Aegis CEO Dr James Smith explains how Aegis uses peace education to break the thread that can lead to mass atrocities.

In this section of our website we look at just some of the major instances of genocide and mass atrocities which have taken place since the early 1900s. This includes the slaughter of the Hereros in German Southwest Africa (now Namibia) in the early 1900s; the Armenian Genocide; the Rape of Nanking, and subsequent mass murder of Chinese civilians by Japanese forces; the Holocaust; the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia; the Bosnian war; the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda; and the ongoing mass atrocities in Darfur, Sudan.

The prevention of genocide and mass atrocities is a global mission, but Aegis does not currently have resources or capacity to address every situation relevant to that mission. We therefore have to make carefully considered strategic decisions about where to focus our efforts – taking particular account of where we have the most significant opportunities to facilitate meaningful change.

At present we are therefore focussed on extending our peacebuilding work from Rwanda to three other countries in proximity: Kenya, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan. We also continue to monitor the situation in Sudan, which has been a focus of much of Aegis’ research and campaigning work since 2005.

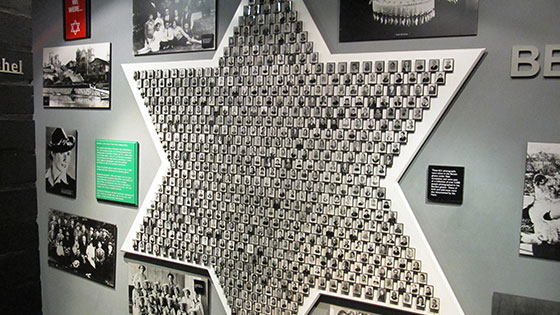

History comes to life through the first-hand testimony of survivors. Facts are revealed, stories told and lost lives restored to meaning.

The story-telling process is vitally important to survivors’ psychology – it helps to lift the emotional burden of the past. As a historical record, testimony reminds current and future generations of the reality of genocide, and is a reminder that it must never happen again.

Testimony is also crucial as evidence in the trials of perpetrators, bringing justice both for survivors and those who have perished.

In crisis situations, testimony from those at imminent risk can be used to help raise awareness in the international community that action must be taken – now.

If we are to understand the causes, circumstances and consequences of genocide, we must listen to the people involved.